Comparing the previously described situation to the previous parts of the chapter, it should be clear that none of the states described in Parts 2.3-4 can be failed states. For each of those states started from the general definition of the state, meaning that their monopoly of the legitimate use of violence was ensured.

However, the previously defined states were indeed a heterogeneous group in terms of state power. This can be best illustrated by turning to the three state types defined by the interpretative layers of legality: corrupt state, captured state, and criminal state. In the case of a corrupt state, what we can speak about is not a failed, but a weak state:[1]

- Weak state is a (de jure) state which is unable to utilize the (monopoly of) legitimate use of violence because of the disobedience of the state apparatus. In other words, while a weak state is regarded as the only legitimate user of violence, the way in which it is used is not determined by the ruling elite but other actors (inside or outside the state apparatus).

The corrupt state is a weak state because while the state apparatus gets orders from the ruling elite (that is, laws are created which the apparatus should enforce) it does not comply with these orders.[2] On the contrary, the members of the apparatus either (a) make compliance (i.e., enforcement of laws) dependent on the payment of bribes, or (b) they start using their state power for predation, that is, takeover of private assets by the means of public administration (grey raiding [→ 5.5.3.1]). Under a weak state, it is typical for members of the public administration to become independent entities and abuse their public positions for private gain. They do this in a disorganized, highly competitive manner, and they can do it either for themselves or—acting as violent entrepreneurs—for certain oligarchs who hire them [→ 3.4.1].[3] Indeed, this phenomenon has been observed mainly in developing states during periods of oligarchic anarchy,[4] which indicates that a failed state is also, ideal typically, a weak state (as well as a corrupt state). The adjectives indeed refer to different aspects of stateness: “failed” means the rulers cannot exercise control over the market for legitimate violence outside the state, whereas “weak” means that the rulers cannot exercise control over its own bureaucracy inside the state (and “corrupt” refers to the presence of bribes).

In contrast, the state is an appealing target to capture if it is not weak, meaning the laws that state capture influences will indeed be enforced. Thus, a captured state assumes at least a normal state:

- Normal state is a state which keeps the monopoly of the legitimate use of violence and is able to utilize it within constitutionally set boundaries. In other words, a normal state is regarded as the only legitimate user of violence and the way in which it is used is determined by the ruling elite, but there are institutional control agents who can enforce formal rules to keep the rulers in check.

Naturally, that the state is constitutionally constrained is not necessary for a capturer; indeed, an unconstrained state can serve the capturer with greater power and therefore it is a more desirable target than a constrained one.[5] However, states in the post-communist region which underwent formal democratization are de jure constitutionally constrained. In order to eliminate these constraints, one has to disable constitutional checks and balances (control mechanisms), to which constitutional power is required—which, however, almost certainly leads to a criminal state. By the dimension of state strength, an unconstrained state may be conceptualized as a strong state:

- Strong state is a state which keeps the monopoly of the legitimate use of violence and is able to utilize it without constitutional constraints. In other words, the ruling elite of a strong state determines the way in which state power is used and there are no institutional control agents who can enforce formal rules to keep the rulers in check.

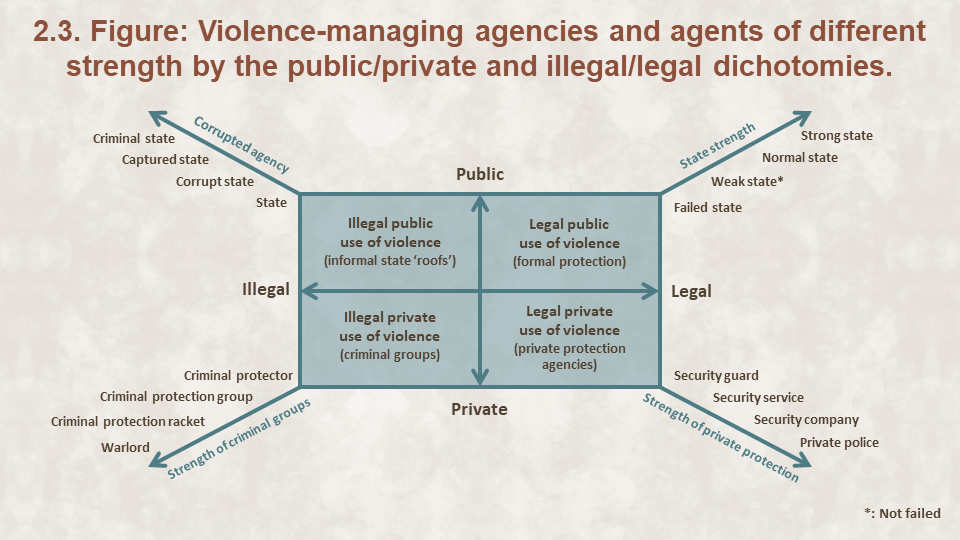

Indeed, using these newly defined state categories, we can draw up a scale of state strength, ranging from failed state through weak and normal state to strong state. The other scale that puts corrupt, captured and criminal states in an ascending order adds the dimension of illegality, that is, when the power of the state is used illegally rather than legally. In other words, with the two scales we can draw up an interpretative framework for the use of violence by public institutions: on the one hand, by how reliably a state can use violence, it can be failed, weak, normal or strong. On the other hand, if this power is used illegally, the weak, normal and strong states become corrupt, captured and criminal states respectively.

This interpretative framework can be augmented by adding the dimension of the legitimate use of violence by private institutions—not the state, but the violent entrepreneurs. Indeed, Volkov suggested a similar framework, differentiating four types of protection by the dichotomies of legality/illegality and public/private nature.[6] However, we can expand the typology of illegal-public, legal-public, illegal-private and legal-private use of violence by specifying 4-4 ideal types of each on ascending scales—which is exactly what we have already done with legal- and illegal-public violence above (Figure 2.3).

As for the subtypes of legitimate private users of violence, we may define four subsequent types of legal violent entrepreneurs as follows:[7]

- Security guard is a legal violent entrepreneur who is hired to provide some service of protection alone.

- Security service is a legal violence-managing agency (violent enterprise) which is hired to provide some service of protection to a single actor or institution.

- Security company is a legal violence-managing agency (violent enterprise) which is hired to provide some service of protection to numerous actors or institutions.

- Private police is a legal violence-managing agency (violent enterprise) which is hired to provide some service of protection to every actor and institution in a certain geographical area.

In contrast, the four types of illegal violent entrepreneurs may be listed as follows:[8]

- Criminal protector is an illegal violent entrepreneur who provides some service of protection alone to a single actor or institution. He is either hired or forces his customers to accept his services.

- Criminal protection group is an illegal violence-managing agency (violent enterprise) which provides some service of protection to a single actor or institution. It is either hired or forces its customers to accept its services.

- Criminal protection racket is an illegal violence-managing agency (violent enterprise) which provides some service of protection to numerous actors or institutions. It forces its customers to accept its services.

- Warlord is an illegal violent entrepreneur who provides some service of protection to every actor and institution in a certain geographical area. He forces his customers to accept his services with the help of a militia (a group of violent actors hired by the warlord).

It should be noted that criminals or criminal groups usually also engage in a variety of other illegal activities beyond protection. However, the logic of conceptualization here is similar to that of interpretative layers, when every state label referred to a single aspect of the state [→ 2.4]. Indeed, the types of illegal violent entrepreneurs given above also refer to only one aspect of criminal actors, namely violent entrepreneurship in the above-defined sense.

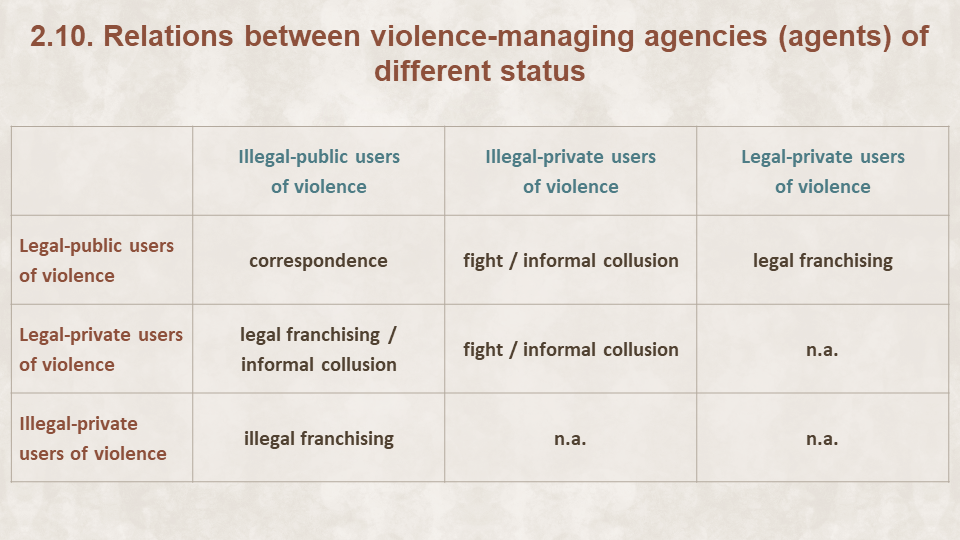

While a criminal protection racket fits the economic definition of (classical) mafia as a private protection agency,[9] the warlord is recognized in the literature as “the leader of an armed band […] who can hold territory locally and at the same time act financially and politically in the international system without interference from the state in which he is based.”[10] Indeed, the warlord acts as the leader of a “state in a state,” and should there be no state above him, he would be the de facto ruler of a strong state.[11] This link between the lower left and the upper right ends of Figure 2.2, as well as the importance of the relation of the warlord to the state, leads us to the question of what kind of connections may exist between the types of violence-managing agencies and agents (Table 2.10). First, as we treat the state as a single unified entity, the connection between the legal and illegal public users of violence can only be that of correspondence. Indeed, this is what we explained already above: the corrupt state corresponds to a weak state, the captured state corresponds to a normal state, and the criminal state corresponds to a strong state.[12] Naturally, if the state functions dominantly legally, every category from weak to strong state corresponds with the ideal type “state,” which is the conceptual starting point of the scale of state corruption. Second, the situation between the legal and illegal private users of violence is different as they are separate entities. By default, they are fighting each other, given that they are on different sides of the law. But alternatively, peaceful coexistence can be imagined between them in cases of informal collusion, formed in spite of the law but perhaps out of necessity or rational consideration of costs and benefits. Third, the same kind of relations of fighting or informal collusion may exist between illegal-private and legal-public users of violence, out of the same considerations. The state may make informal peace with a warlord, who is at odds with the law but against whom the state realizes a war would be too costly.[13]

Fourth, public actors—both legal and illegal—can legally franchise state coercion to private-legal users of violence. Indeed, the state can hire private security guards, services or companies to protect public actors or property, and can even franchise the function of protection to a private police force if the state is unable to hold a territory by its own forces. Indeed, the failed state of Russia in 1992 adopted “the pivotal Law on Private Protection and Detective Activity, which legalized private protection agencies and for several years formally sanctioned many of the activities already pursued by racketeering gangs and other agencies. It turned many informal protective associations into legal companies and security services, and their members into licensed personnel.”[14] This means that when the state failed and protection was taken over by then illegal violent entrepreneurs, the state decided to formalize this relationship and created a legal environment where illegal actors became legal violent entrepreneurs, with formal relation to the state.

What is important to notice here is that, in case of legal franchising, the state’s monopoly on the legitimate use of violence does not break down. Rather, it is more like decentralizing a previously centralized state activity, which still remains a monopoly of the state and can be pursued only by those who are hired by—in this case, get franchise from—the monopolist. Similarly, the state does not become a de facto failed state in case of illegal franchising of state coercion either, which takes place when relations are formed between illegal-public and private users of violence. State coercion may be illegally franchised when the illegally acting public actor (typically the chief patron in a criminal state) wants to use the kind of violence that would be politically harmful to perform via formal/public institutions. In this case, the illegal-public actor can use black coercion [→ 4.3.5.4] which means illegally franchising state coercion to legal-private actors—such as football ultras—or illegal-private actors—such as paramilitary groups or the criminal underworld.[15] Indeed, illegal-public users of violence might even franchise state coercion to warlords if the country is especially big and the chief patron does not have enough power to reach certain regions.

[1] Cf. Malejacq, “Warlords, Intervention, and State Consolidation.”

[2] Naturally, corruption is not the only possible case for state weakness, which can also be the result of lack of bureaucratic culture, among other things. See Huntington, Political Order in Changing Societies, 61.

[3] Markus, Property, Predation, and Protection.

[4] Markus, “Secure Property as a Bottom-Up Process.”

[5] Cf. Holcombe, Political Capitalism, 2018, 246–49.

[6] Volkov, Violent Entrepreneurs, 167–73.

[7] Cf. Varese, The Russian Mafia, 55–72.

[8] For a more comprehensive analysis of illegal violent entrepreneurs, see Berti, “Violent and Criminal Non-State Actors.”

[9] Gambetta, The Sicilian Mafia.

[10] MacKinlay, “Defining Warlords.”

[11] Mancur Olson famously argued that the first states were founded by warlords—or “stationary bandits,” as he calls them—who started acting as tyrants and set up institutions to exercise their power over a geographical area for a longer period of time. Olson, Power And Prosperity.

[12] If we wanted to divide the state up to legally and illegally acting actors, we could say the legally acting ones are at antagonistic relation with the illegally acting actors, since a more indulgent attitude from a legal actor is itself illegal (so committing it would make the legal actor illegal, too).

[13] Russell, “Chechen Elites: Control, Cooption or Substitution?” Also, cf. Mukhopadhyay, Warlords, Strongman Governors, and the State in Afghanistan.

[14] Volkov, Violent Entrepreneurs, 24.

[15] Stephenson, “It Takes Two to Tango.