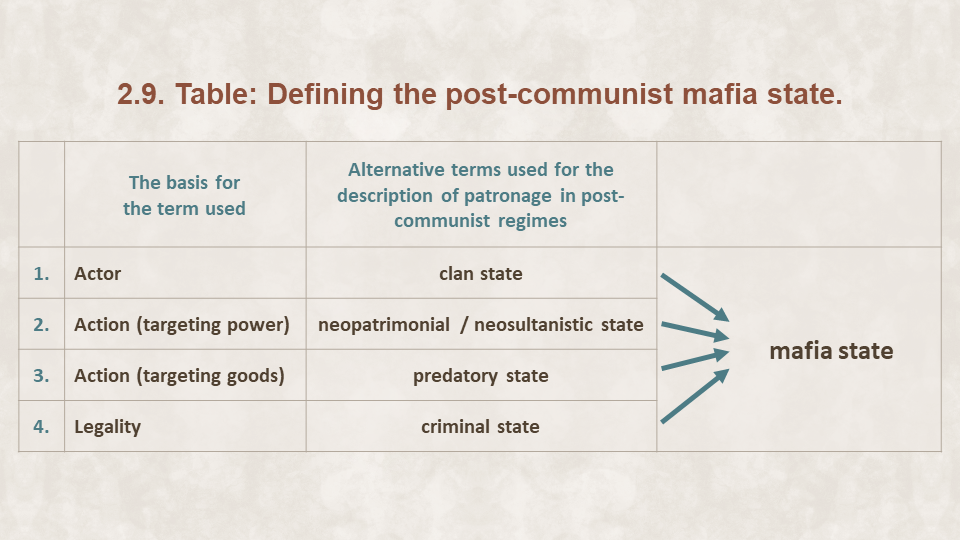

What needs to be seen with respect to the state types above is that they are only partial types. That is, they identify a state only from one aspect while not reflecting on the given state’s other aspects, or the three other dimensions beside their own one. This also points to the way to create more complete state types: because the four sets of interpretative layers refer to different aspects of state functioning, their concepts can be used simultaneously for the description of a state running on the principle of elite interest. For instance, a state that is rent-seeking can also be captured, patronal and neopatrimonial. While not every kind of combination is possible, following the congruence between definitions of various states,[1] one that is not only possible but constitutes the ideal typical state of patronal autocracies is the mafia state—combining the most extreme variants (the lowermost interpretative layers) of each dimension of states running on the principle of elite interest (Table 2.9).

Based on the definitions of the state types from the lowermost interpretative layers, we can outline the definition of the mafia state as follows:

- Mafia state is a state ruled by an adopted political family, patrimonializing political power in a democratic environment and using it in predatory ways, routinely stepping over formal laws and operating the state as a criminal organization. In other words, the mafia state is a combination of a clan state, a neopatrimonial/neosultanistic state, a predatory state, and a criminal state.

Journalists have used the term “mafia state” for two kinds of states: (a) which have close ties to organized crime, captured to some extent by criminal syndicates and involved in various illicit activities (drug trade, human trafficking etc.);[2] and (b) which are particularly aggressive and use brutal, “mafia-like” methods to keep up their rule.[3] In our scholarly discussion, however, the term is defined in a way that:

- a mafia state does not have to have ties to organized crime, nor be captured or led by a criminal syndicate;

- a mafia state’s ruling elite does not have to originate from organized crime (although that is a possibility);[4]

- a mafia state does not have to engage in illicit activities typically associated with mafias (drug trade, human trafficking etc.);

- a mafia state does not have to use brutal, bloody means for everyday operation.

Indeed, the way we define it, a mafia state is not a symbiosis of state and organized crime but a state which works like a mafia—not in terms of illicit activities per se but in terms of internal culture and rulership. In other words, the “mafia state” is not an historical analogy to the Sicilian or American mafia but a concept that focuses on the definitive feature of the mafia as a sociological phenomenon. For the purposes of our framework, we identify the mafia’s definitive features through the work of Eric Hobsbawn, who circumscribes the mafia in his classic work Primitive Rebels. According to him, the definitive sociological feature of the mafia is that it is a violent, illegitimate attempt at giving sanction to the pre-modern powers vested in the patriarchal head of the family. The mafia is an adopted family, “the form of artificial kinship, which implied the greatest and most solemn obligations of mutual help on the contracting parties.”[5] At the same time, the mafia Hobsbawn describes is the classical mafia—we may say, a form of organized underworld—which exists in a society established along the lines of modern equality of rights. Thus, the patriarchal family in this context is a challenger to the state’s monopoly of violence, while the attempt to give sanctions to the powers vested in the family head is being thwarted, as far as possible, by the state organs of public authority. In short, the mafia is an illegitimate neo-archaism.[6]

In contrast, the mafia state—we may say, the organized upperworld—is a project to sanction the authority of the patriarchal head of the family on the level of a country, throughout the bodies of the democratic institutional system, with an invasion of the powers of state and its set of tools. Compared to the classical mafia, the mafia state realizes the same definitive sociological feature in a different context, making the patriarchal family not a challenger of state sovereignty but the possessor of it. Accordingly, that is achieved by the classical mafia by means of threats, blackmail, and—if necessary—violent bloodshed, in the mafia state is achieved through the bloodless coercion of the state, ruled by the adopted political family. In terms of the patterns of rulership, the exercise of sovereign power by the “Godfather” (the chief patron), the patriarchal family, the household, the estate, and the country are isomorphic concepts. On all these levels, the same cultural patterns of applying power are followed. Just as the patriarchal head of the family is decisive in instances disposing of personal and property matters, also defining status (the status that regulates all aspects of the personal roles and competencies among the “people of his household”), so the head of the adopted political family is leader of the country, where the reinterpreted nation signifies his “household” (patrimonium). He does not govern, but disposes over people; he has a share, he dispenses justice, and imparts some of this share and justice on the “people of his household,” his nation, according to their status and merit. Furthermore, in the same way that the classical mafia eliminates “private banditry,”[7] the mafia state also sets out to end anarchic corruption, which is replaced by a centralized and monopolized enforcement of tribute organized from the top. In essence, the mafia state is the business venture of the adopted political family managed through the instruments of public authority.

As it can be seen from the previous paragraph, the description of the mafia state incorporates the concepts previously associated with political-economic clans, patrimonialism, and predation (top-down disposition of property relations). The element of criminality is implied, too; although the adopted political family uses the means of public authority, it also commits illegal acts. After all, no law prescribes that public monies should always go to the same person or group (of loyal clients), nor that the instruments of public authority should intensify supervision and inspections against targets or enemies of the adopted political family (let alone upon the chief patron’s order). To be more precise, the statutory definition of crimes committed by the mafia state’s leading political eliteinclude extortion, fraud, embezzlement, misappropriation, money laundering, insider trading, bribery of officials (both the active and passive forms of these last two), abuse of authority, buying influence, racketeering, etc.[8] This is exactly why the mafia state disables prosecution, or rather takes it over and activates it against targets only [→ 4.3.5.2]. In effect, criminality in the mafia state is split into authorized and unauthorized illegality, where the latter is prosecuted and the former is not [→ 5.3.4]. Thus, the accusation of criminality is done not from an external moral position but according to the regime’s existing (criminal) law, the enforcement of which is hindered by the full appropriation of the state by the adopted political family.

[1] The intersections between the interpretative layers of legality and state action targeting property will be shown in Table 5.9 in Chapter 5.

[2] Naím, “Mafia States”; Dickie, Mafia Republic; Wang and Blancke, “Mafia State.”

[3] Ayittey, “The Imminent Collapse of the Nigerian ‘Kill-and-Go’ Mafia State”; Harding, Mafia State.

[4] Cf. Miller, Moldova under Vladimir Plahotniuc. Also, see “criminality-based clan” in Chapter 3 [→ 3.6.2.1].

[5] Hobsbawm, Primitive Rebels, 55.

[6] There exist other definitions of “mafia”: for instance, economists define it as a private agency of protection (see Gambetta, The Sicilian Mafia.). Obviously, we do not use the concept in that sense. The reason we adopted a different definition, and particularly Hobsbawn’s, is precisely that we want to define the mafia state by the features he designated as definitive. Definitions that emphasize other features may well work in other contexts, but in the context of this book, “mafia” should be understood only in the sense we defined it above.

[7] Hobsbawm, Primitive Rebels, 40.

[8] Magyar, “The Post-Communist Mafia State as a Form of Criminal State.”