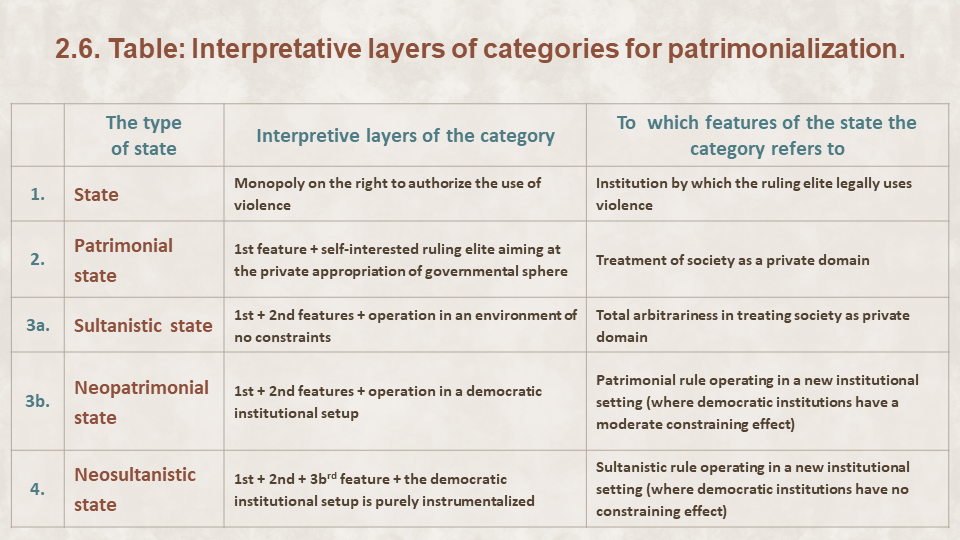

The second dimension of categorization is the action of the ruling elite aiming at using state institutions for elite interest. The interpretative layers and the related concepts can be seen in Table 2.6. Our conceptual starting point is, again, the state led by the ruling elite, possessed of the monopoly of legitimate use of violence. Further categories can be defined as follows:

- Patrimonial state is a state which runs on the principle of elite interest, represented by a ruling elite that aims at treating society as a private domain in the formal institutional setup that is given.

- Sultanistic state is patrimonial state where the formal institutional setup has no constraining effect on the ruling elite (or rather the head thereof), which can pursue its elite interest and treat society as its private domain at its whim.

- Neopatrimonial state is a patrimonial state where the formal institutional setup is democratic in form (featuring multi-party elections, the constitutional separation of the branches of power, and the legal recognition of the free enterprise system and basic human rights). This setting has a limited capacity to constrain the patrimonialism of the ruling elite, or at least the practices of the ruling elite are influenced and refined by the institutional setup (which, in turn, gets corrupted by the ruling elite).

- Neosultanistic state is a neopatrimonial state where the formal, democratic institutional setup has no constraining effect on the ruling elite (or rather the head thereof). In such a system, the ruling elite can pursue its elite interest and treat society as their private domain at its whim, whereas the institutions of democracy become pure instruments of patrimonialism.

The use of these terms attempt to convey the sui generis traits of post-communist regimes through the adaptation and reformulation of Weber’s typology for systems of rule. “Where domination is primarily traditional, even though it is exercised by virtue of the ruler’s personal autonomy, it will be called patrimonial authority,” writes Weber. He continues: “where it indeed operates primarily on the basis of discretion, it will be called sultanism” (emphasis added).[1] Our main modification to this definition is making the dimension of institutional setup explicit. For although the terms in their original form capture what we described above as the principle of elite interest, it is the institutional setup in which this principle is enforced that distinguishes these states from each other. In patrimonial states, lordship is explicit and it is limited by traditional constrains of such institutions. In sultanistic states, such constraints that effectively limit the exercise of power do not exist, and usually it is the head of the ruling elite who disposes over the state at his whim (hence the word “sultan”). Thus, even intra-elite constraints, otherwise taking the form of any kind of entitled body of decision-making, are lacking [→ 3.6.2]. This is why sultanism is widely recognized as an extreme form of patrimonialism.[2]

Attaching the prefix “neo-“ to Weberian terms may not be as precise as a substantive adjective would be, that is, an adjective expressing the actual content of these states’ novelty. But we still adopt these terms because (1) they signify that these states prevail in different historic eras than the original regimes that Weber analyzed and (2) they are already familiar in existing literature (see Box 2.3).[3] Substantively, “neopatrimonial” refers to a change in the institutional setup: that patrimonialism is no longer explicit, and it is no longer limited by traditional (hard) constrains, but it operates behind the façade of democratic institutions, which provide legal (soft) constraints. In neopatrimonial states, the ruling elite complies, more or less, to an existing legal framework, which it changes continuously to fit the aim of serving its elite interests better [→ 4.3.4]. Yet laws do influence neopatrimonial rulers, who have to develop more refined ways of seeking elite interest to conceal their efforts in a democratic environment, where the rulers rely on electoral civil legitimacy [→ 4.2].

| 2.3. Box: On the concept of neopatrimonialism. “Guenther Roth was first to point out the emergence of the new modern forms of patrimonial domination […] in his famous article ‘Personal Rulership, Patrimonialism, and Empire-Building in the New States’ published in 1968 in the ‘World Politics’ magazine. […] Shmuel Eisenstadt, who in a number of his works developed a complex theory of neopatrimonialism, made next step in the development of this concept. […] One can identify three main principles of the neopatrimonial systems’ functionality: – Political center is separated and independent from the periphery, it concentrates political, economic and symbolic resources of the authority, while simultaneously closing access to all other groups and levels of the society to these resources and positions of control over them; – The state is managed as a private possession (patrimonium) of the ruling groups – holders of the state authority, which privatize various social functions and institutions, making them sources of own private profit; – Ethnic, clan, regional and family-relative ties do not disappear, but are reproduced in the modern political and economic relations, determining methods and principals of their functioning.” – Oleksandr Fisun, “Neopatrimonialism in Post-Soviet Eurasia,” in Stubborn Structures: Reconceptualizing Post-Communist Regimes, ed. Bálint Magyar (Budapest–New York: CEU Press, 2018). |

Neosultanistic states, on the other hand, are composed of purely instrumentalized formal institutions. In other words, the formal institutional setting here has no influence or constraint over the ruling elite, and methods of rule need not be refined any futher. For if a law contradicts the principle of elite interest, it will either be changed or simply disregarded [→ 4.4.3.3]. Civil legitimacy in these systems becomes pure show: popular elections are held, but in case of non-favorable results, the ruling elite commits electoral fraud without hesitation [→ 4.4.3.2].

It may be noticed that, conceptually, neosultanistic state could also be regarded as a subtype of sultanistic state, to which the feature of operation in a democratic institutional setup should be added then. Although such ordering would be equally logical it would be less useful analytically, for in the post-communist region it is a neopatrimonial state, and not a sultanistic one, that can typically evolve into a neosultanistic state [→ 4.3.3.3]. As Houchang Chehabi and Juan Linz observe, using the term neosultanistic “[has] the advantage of not only distinguishing [such states] from the Weberian use of the term ‘sultanism,’ but also maintaining the logic of Weber’s terminology; […] just as for Weber the transition between patrimonialism and sultanism is ‘definitely continuous,’ neosultanistic regimes are an extreme version of neopatrimonial forms of governance.”[4]

[1] Weber, Economy and Society, 232.

[2] Guliyev, “Personal Rule, Neopatrimonialism, and Regime Typologies,” 577–80.

[3] Cf. Gerring, “What Makes a Concept Good?”

[4] Chehabi and Linz, Sultanistic Regimes, 6.