2.2.2.1. Defining elites and non-elites

The notion of elites can be interpreted meaningfully only in comparative terms. For the existence of an “elite” must imply the existence of the “non-elite,” that is, people who are part of the society but are outside elite circles. Elites, in the classical sense of the term, are defined as “the best” in some respect and the non-elites, as the ones who are worse than the elites.[1] A narrower definition, used in the mainstream literature, also assigns to elites the feature of having “more social weight than others because their activities have greater social significance.”[2] Such elites are typically observed as “tiny but powerful minorities […] made up of autonomous social and political actors who are interested primarily in maintaining and enhancing their power.”[3] In short, this second definition underlines that the members of the elites have significant influence over the lives of the non-elites and that they can also use this influence to attain their own ends, vis-à-vis the ends of the non-elites.

For the purposes of our framework, we give the following operational definition for elite and non-elite:

- Elite is a group of people, related or unrelated to each other, who are leading actors in their walk of life, that is, having greater influence over the lives of others in the same walk of life than the influence of those people over them. (“Those people” are the non-elite.) This leading position, which can also be termed “power,” stems from having extraordinary qualities, such as wealth, excellence, or high (formal) position in a hierarchy.

- Non-elite is a group of people, related or unrelated to each other, who are following actors in their walk of life, that is, having lesser influence over the lives of others in the same walk of life than the influence of those people over them. (“Those people” are the elite.) This following position stems from having ordinary or poorer qualities, such as lack of wealth or having a low (formal) position in a hierarchy.

The expression “walk of life” may refer to any part of the society, from its entirety to certain segments of the private or public sector. Indeed, the definition of “walk of life” is not an independent one but it is circular: whatever part of society, where some people have greater influence over the others than vice versa, can be analytically isolated as a walk of life, divided into the two general groups of the elite and the non-elite.

Following Vilfredo Pareto’s classical theory of elites,[4] we can divide elite groups themselves into two general categories: non-ruling elites and the ruling elite.

- Non-ruling elite is an elite without coercive (state) authority. In other words, a non-ruling elite can exercise its influence over its walk of life only through non-coercive means, such as persuasion, leading by example, or market transactions. Typically, there are numerous non-ruling elites in a society.

- Ruling elite is an elite with coercive (state) authority. In other words, a ruling elite can exercise its influence over its walk of life—the society itself, living under the rulers’ authority—through coercive means, such as law enforcement. Typically, there is only one ruling elite in a society.

That typically there is only one ruling elite in a society corresponds to the situation that a people or society lives under a single state, possessing a local monopoly of the legitimate use of violence. However, as we are going to see in later parts of the chapter, this is not necessarily the case. The state may fail to maintain its monopoly of legitimate violence and degenerate into a mere violence-managing agency among many, who are hired by people—legally or illegally—to provide protection and other violent services [→ 2.5]. In this case, we could speak about more than one ruling elite, although in the following discussion “ruling elite” will be used exclusively in the context of stable states to avoid confusion.

2.2.2.2. Patronalism, informality, and the general character of ruling elites in the three polar type regimes

While the members of an elite in general need not be related to each other in any sense, besides belonging to the same walk of life, the members of the ruling elite are always linked. For in a state, the access to coercive means is monopolized, and those who can access it must coordinate their activities. In fact, coordination (which implies the presence of links) is required to seizing power in the first place, both in cases of non-democratic takeovers and democratic transfers of power [→ 4.3.2].

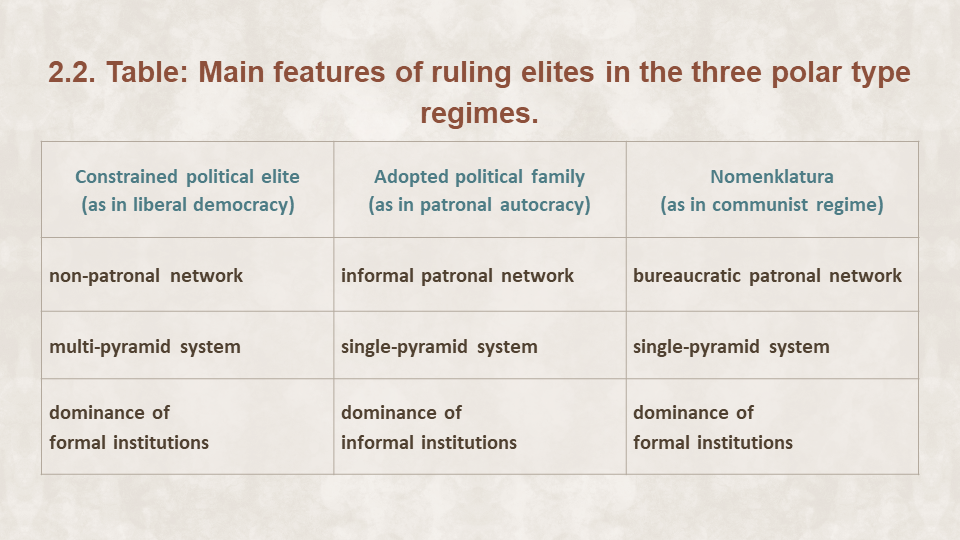

On the basis of the stubborn-structures argument, the two main aspects by which ideal type ruling elites can be conceptualized for the post-communist region are patronalism and formality (Table 2.2). As for patronalism, we can define the dichotomy of patronal and non-patronal connections as follows:[5]

- Patron-client relationship (patronal connection) is a type of connection between actors where people are connected through vertical chains of command with a strong element of unconditionality and inequality in power. In a patron-client relation, one of the participants—the client—is a vassal (i.e., subordinate) of the other—the patron. A patronal connection is a coercive relationship, involving no free exit from the network (and often no free entry to the network either).

- Voluntary relationship (non-patronal connection) is a type of connection between actors where people are connected through horizontal relationships between equal parties. In a voluntary relationships, there is no vassalage (i.e., subordination) and no party is forced to obey another. A non-patronal connection is a non-coercive (voluntary) relationship, involving free exit as well as free entry.

In these definitions, the vertical-horizontal dichotomy is used, where the former refers to vassalage, subordination and asymmetric relationship and the latter, to the lack thereof. Defining these, we built on the notions of coercion and voluntariness introduced above, along which we also use the dimension of freedom of exit from the relation (network). This refers to whether the members of the network would face coercion should they leave the network (unfree exit) or they would not (free exit) [→ 6.2.1]. Although they can also be hierarchical, voluntary relationships feature free entry and exit in this sense, whereas patronalism implies a tyrannical hierarchy with no free entry and exit.

As for formality, we give the following operational definitions for formality and informality:

- Formality is a characteristic feature of a social connection and refers to having a legal and openly admitted form. In other words, an institution—that is, a humanly devised constraint that structures social interaction—is regarded as formal if its rules are written down, in congruence with effective law, and are made openly accessible to the majority of the population.

- Informality is a characteristic feature of a social connection and refers to not having a legal and openly admitted form. In other words, an institution—that is, a humanly devised constraint that structures social interaction—is regarded informal if its rules are not written down and are not made openly accessible to the majority of the population (therefore its rules may or may not be congruent with effective law).

Indeed, formality or informality of institutions can be simplified—for the purposes of our framework[6]—to whether they have a form that is legally recognized. Primarily, the state and the ruling elite that is legally authorized to use state power are formal as far as their position is legally defined, whereas if a political, economic or societal actor fulfills roles that are not legally recognized then (1) they are regarded informal as far as those roles go and (2) the institution that involves that legally non-recognized, unwritten role is also regarded informal. As for “institutions,” we use the term in the sense it appears in the definitions: humanly devised constraints that structure social interaction and generate regularities of behavior.[7] To be more precise, “humanly devised constraints” include regulations (de jure rules), actual practices (de facto rules), and narratives (storytelling),[8] although we will use the concept in a broader sense for formal and informal elite groups, governments and state agencies as well.

Applying the above-defined dichotomies to ruling elites, we should first differentiate two types of ruling elites—non-patronal and patronal:

- Patronal ruling elite is a ruling elite where the members are connected, formally or informally, through patron-client relations. The patronal ruling elite takes a pyramid-like structure of obedience (single-pyramid system), every member being part of a hierarchy subordinated to the chief patron.

- Non-patronal ruling elite is a ruling elite where the members are connected, formally or informally, through voluntary connections, that is, horizontal relationships between equal parties. The non-patronal ruling elite is composed of numerous factions with certain degrees of autonomy (multi-pyramid system), avoiding the authoritarian rule of a single leader.

In a liberal democracy, the ruling elite is non-patronal. Stemming from the definition of constitutional state [→ 2.3.2], numerous autonomous factions exist, usually within the governing party but certainly within the state, in the form of separated branches of power [→ 4.4.1]. The autonomy of the latter is guaranteed by the constitution, whereas the autonomy of factions within the governing party can be guaranteed by the plurality of resources, that is, that the party leadership cannot possess every available resource, economic or political. Indeed, in liberal democracies there is “open access” to political and economic resources, to use the expression of Douglass North and his colleagues from Violence and Social Orders [→ 2.4.6, 6.2.1]. As they write, in regimes like liberal democracy “political parties vie for control in competitive elections. The success of party competition in policing those in power depends on open access that fosters a competitive economy and the civil society, both providing a dense set of organizations that represent a range of interests and mobilize widely dispersed constituencies in the event that an incumbent […] attempts to solidify its position through rent-creation, limiting access, or coercion.”[9]

What is possible even in this ideal typical model is that, within a liberal democratic regime, certain segments of the state are captured temporarily where the capturer, gaining access to coercive (state) means, becomes an (informal) part of the ruling elite and the captured one becomes his vassal. In such cases, the capturer-captive relation takes the form of a patron-client relation. However, such phenomenon can only be partial and, more importantly, it features only a patronal chain, not a patronal network. For the latter includes, by definition, a large number of patronal chains, organized in a pyramid-like fashion.[10]

Since factions themselves usually have internal hierarchies, they can be described as “pyramids,” whereas a high number of competing factions, a “multi-pyramid system.”[11] In contrast, both communist dictatorship and patronal autocracy are characterized by single-pyramid systems of patronal ruling elites. As Hale writes, in single-pyramid systems the main networks of power “are gloomed together to constitute a single ‘pyramid’ of authority under the chief patron who is usually regarded as the country’s leader, and any networks remaining outside this pyramid are systematically marginalized, widely regarded as unable to pose a credible challenge to the authority of the dominant group.”[12]

In a communist dictatorship, the single-pyramid is built on two pillars. First, the aim of the Marxist-Leninist party to engineer society by the means of state coercion, from which it follows that the bureaucratization of society and that the single-pyramid itself is, too, a bureaucratic network. Second, the state party monopolizes all the available resources and creates a merger of powers, which means no other pyramids are viable in such a system, nor any member of the ruling elite can be outside of the party state and its formal institutional setup. The nomenklatura, as the ruling elite of communist dictatorships is commonly called, is a register of ruling positions, including party positions—the political decision-makers on national and local level—and administrative positions—decision-makers in state companies and other places where central plans are executed.[13] For the allocation of economic and political resources for people on the lower levels is centralized at higher levels [→ 5.6.1], a strong element of inequality in power appears between members of the hierarchy indicating the presence of patron-client relations in a bureaucratic form. Informal networks of patronage also form along these formal positions, and informal connections cannot provide more power to someone than what he is given as a link in a bureaucratic patronal chain of the network.

In the nomenklatura, it is formal positions that exist primarily and chosen people are assigned these positions secondarily. In other words, the bureaucratic setting is more permanent than the list of the people who are chosen to fill it. In the ruling elite of patronal autocracies, the case is the other way around. For it is the patronal network, the so-called adopted political family and its members, which are primary. In fact, the network typically comes into being outside the state and once power is seized, formal positions are tailored to the family or the wishes of its members. Therefore, the adopted political family is the point of reference, and it is the list of people within the patronal hierarchy that is more permanent than the formal institutional setup. While in the nomenklatura, where positions are primary, one person is usually assigned to one single position on a certain level of the bureaucratic hierarchy, a member of the adopted political family can have many different positions on various levels of the formal hierarchy.

This leads us to focus on the second dichotomy of formality and informality. The adopted political family is a largely informal phenomenon, meaning not only that its effective hierarchy is situated outside (or above) the formal institutions of the state, but also that the adopted political family has no legal form. The actual decisions are removed from the—nevertheless strictly controlled—bodies of the “ruling” party and, through the chief patron, transferred to the patron’s court, which lacks formal structure and legitimacy [→ 3.3.2]. Patron-client relations, keeping the network together and making the power of the chief patron effective, exist not in a bureaucratic form but out of similar reasons as they do in communist dictatorships—namely, “the monopolization by the patrons of certain positions that are of vital importance for the clients.”[14] This relates primarily to political resources—the public sector—but it also extends to economic resources—the private sector. The adopted political family also uses state coercion as its primary means; however, the branches of power are formally separated, and only informally connected in a patronal autocracy [→ 4.4.3]. Through the full appropriation of the state as well as the arbitrary and unconstrained use of the instruments of public authority, the informal patronal network reaches down to virtually every level of the society.[15]

The informality of the adopted political family is different from the informal phenomena associated with communist and democratic ruling elites. As we mentioned earlier, informal relations did exist between the members of the nomenklatura in communist dictatorship, including personal relations, informal oral commands and handshake agreements [→ 1.4.1].[16] In liberal democracies, informality appears on the level of elites in three forms: (1) informal relations, like acquaintance and friendship which contribute to the integration of political and economic elites;[17] (2) informal agreements, particularly ones concluded prior to formal (e.g., parliamentary) debates;[18] and (3) informal norms, like mutual toleration and institutional forbearance, which have been noted as essential to the healthy functioning of liberal democracy and its resilience against autocratic tendencies.[19] Such informalities are different from the informality of the adopted political family, for in liberal democracies and communist dictatorships:

- informality exists around formal institutions, meaning (1) informal relations presuppose the formal rank of the actor, that is, they are formed between formal actors qua formal actors, and informal relations do not give them extra political competences or power their formal position does not entail (especially in communist dictatorship), (2) informal norms help the functioning of formal institutions as they indeed mean routinization of a cultured “best practice,” ingrained in informal patterns of behavior (especially in liberal democracies), and (3) informal networks in the elite do not reach beyond the boundaries of the formal institutional setting (equally important in both regimes). Therefore, formality has supremacy over informality. In contrast, in patronal autocracies informality overrules formal institutions, meaning (1) informal relations do not presuppose the formal rank of the actor and may enable someone with no political position to have political power, (2) informal networks use formal institutions to the extent they are needed, but otherwise informality replaces formality as the primary determinant of power, law and elite behavior, and (3) informal ties are between those with as well as without formal power, and the resultant network extends beyond the boundaries of the formal institutional setting;

- informal agreements do not deprive formal bodies of their de facto decision-making role and decision-making remains within the confines of formal bodies. This is obvious in the case of communist dictatorships, where the subject of Kremlinology was precisely the informal relations within the nomenklatura and between the party leaders, and no informal positions of power held by people outside the nomenklatura existed. In liberal democracies, when agreements are concluded prior to formal debates and therefore outside the formal bodies, the point is secrecy, that is, keeping the real motives and bargains from the public. But those who make the decisions de facto and de jure are the same: the same people who have formal right to decide make the informal deals as well (in line with the previous point). In contrast, in patronal autocracies formal decision-making bodies become transmission-belt organizations, deprived of real power in favor of the adopted political family. One set of informally connected people make the decisions, some (a) with de jure political power but reaching beyond their formal competences (like a president/prime minister chief patron) and some (b) without de jure political power (like inner-circle oligarchs [→ 3.4.1]), while those who represent and vote on these decisions in the formal (transparent) institutional realm are dominantly political front men, who do not take decisions but simply manage the decisions taken by the political family [→ 3.3.8];

- informal norms are respected but are typically not coercive, meaning those who do not respect an informal norm might be regarded as strange or subversive,[20] and people may not want to associate with them, but no one is forced into following an informal norm (especially in liberal democracies). Similarly, informal intra-elite relations in liberal democracy may be friendships or acquintances, which are not coercive hierarchies between formally independent elite actors. In contrast, informal relations are coercive in the adopted political family as they indeed embody patron-client relations, enforced by the chief patron through the instruments of public authority (selective law-enforcement as well as discretional state coercion and intervention [→ 2.4.6, 4.3.5, 5.4]).

Throughout the book, our primary concern when speaking about informality will be informal practices, defined by Ledeneva as “an outcome of players’ creative handling of formal rules and informal norms—players’ improvisation on the enabling aspects of these constraints. [Informal practices are] regular sets of players’ strategies that infringe on, manipulate, or exploit formal rules and […] make use of informal norms and personal obligations for pursuing goals outside the personal domain.”[21] In liberal democracies, informal practices appear as deviances, such as in case of voluntary corruption [→ 5.3.2.2] and democratic legalism [→ 4.3.5.3]. Informal practices in patronal autocracies appear as constituting elements, as in case of coercive corruption [→ 5.3.2.3], politically selective law enforcement [→ 5.3.2.2], and making law in general conditional upon its congruence with an informal “shadow norm” [→ 4.3.4.2].

To sum up, we can see that in both liberal democracy and communist dictatorship there is a dominance of formal institutions, be they party or state, single- or multi-pyramid systems. In contrast, a patronal autocracy is characterized by a dominance of informal institutions. To be more precise, we may adopt the term “informal organization” from Levitsky and Gretchen Helmke,[22] which refers to an informal entity that (1) is organized into a network and (2) has a different identity from formal institutions. Thus, in a patronal autocracy what we can see is indeed the supremacy of one specific informal organization—the informal patronal network of the ruling elite, that is, the single pyramid of the adopted political family.

2.2.2.3. Stratification of patronal pyramids: one-tier and multi-tier single-pyramids

While power is concentrated in the hands of their top leadership, single-pyramid arrangements do have an internal stratification. First, they have a certain hierarchy, which—as their name suggests—is a pyramid-like construct with the most powerful actor at the top and the least powerful actors at the bottom. However, it is not the actors who are in a strict descending order of power but rather the layers of patronal hierarchy. Each layer consists of equals in terms of power,[23] and, in a pyramid-like fashion, the least powerful but most populous layer is at the bottom, the second least powerful and most populous one is one-level higher, and so on until the top layer. Indeed, the top layer is the only one where there are no equals but only the top patron, whose power is unique and unmatched ideal typically [→ 4.4.3.2]:

- Top patron is the head of a patronal network. He is singularly powerful, meaning there is no one like him in the network in terms of power and influence over the network’s members.

When we talk about a single-pyramid arrangement, the top patron will be called chief patron [→ 3.3.1]. Subordinated to the top patron, there are also sub-patrons who constitute the links between the layers of the patronal hierarchy:

- Sub-patron is a client of the top-patron who also has clients below him in the same patronal hierarchy. There are equals to the sub-patron, meaning his power is matched by others in the network, although he typically has clients who answer only to him (besides the chief patron, ultimately).

Turning to ruling elites and single-pyramids, in communist dictatorships every layer is formal and there is a strict, legally binding hierarchy that is expressed in the nomenklaturists’ formal ranks.[24] In contrast, the layers in patronal autocracy are informal and the formal ranks of the members of the adopted political family do not necessarily express their de facto position in the informal patronal network. As for de facto position, while there may be several layers of adopted political families the most important line of division is between those with direct contact to the chief patron and those with no direct contact. Given their personal relationship, the former have more power and influence over the top patron as well as the whole patronal network than the latter (the layer of people with direct contact is to be called the patron’s court [→ 3.3.2]). For example, Stanislav Markus analyzes Russian chief patron Vladimir Putin’s network and differentiates three important groups: (1) Putin’s personal friends (“connected to him through the Ozero dacha cooperative, his hobbies, and his career”); (2) the so-called silovarchs (“business elites who have leveraged their networks in the FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) or the military to amass extreme personal wealth”); and (3) outsiders (“super rich […] who are not personally connected to Putin, the military, or the FSB”).[25] Although all of these groups are important and enjoy the privileges of belonging to a single-pyramid patronal network, they are different in terms of proximity to power and therefore (1) influence over Putin’s decisions and (2) access to economic resources [→ 6.2.1].[26]

Inside the single-pyramid, competition exists within and perhaps between layers but not toward the chief patron. In an adopted political family, the sub-patrons are subordinated to the principle of elite interest and try to capture as many political and economic resources they can, and the equals at every level of the patronal hierarchy compete with each other in a zero-sum game.[27] But they must not challenge the chief patron. The chief patron allows competition between his clients, who can mobilize their own clients and use (state) resources in the domain that they are assigned to manage.[28] However, over every action the chief patron has a “veto right,” that is, he can intervene with the means of public authority, whereas challenging him counts as disloyalty which is always avenged [→ 3.6.2.4]. This is different from bureaucratic single-pyramids because, while challenging the top patron, the general party secretary, is certainly forbidden there, too, it is not disloyalty to his person that is punished but disloyalty to the state party [→ 3.3.5].

Besides layers, single-pyramid networks may also have tiers. Simply put, a tier refers to relative autonomy. In so-called multi-tier single-pyramids, a patron on the lower-tier (1) is in a subordinate position to the top patron of the upper tier—that is, the chief patron—but (2) he has his own network of clients and he can dispose over them as well as over the political and economic resources of a (local) government with practically no interference. Naturally, he yields resources and compliance to the top patron but, in return, he enjoys significant autonomy within his own domain. Charles Tilly refers to this kind of relationship as brokered autonomy [→ 5.3.4.2].[29] Multi-tier single-pyramids exist primarily in patronal autocracies with large territory—like Russia—whereas in smaller patronal autocracies—like Hungary—a one-tier single-pyramid exists with no lower level in a brokered-autonomy status [→ 7.4.3.1].

[1] Keller, “Elites.”

[2] Keller, 26.

[3] Higley and Pakulski, “Elite Theory versus Marxism,” 230.

[4] Pareto, “The Governing Elite in Present-Day Democracy.”

[5] Eisenstadt and Roniger, “Patron—Client Relations as a Model of Structuring Social Exchange.”

[6] For a literature review and more overarching understanding of informality, see Ledeneva, The Global Encyclopaedia of Informality, Volume 1:1–5.

[7] North, “Institutions”; Greif, Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy.

[8] Lowndes and Roberts, Why Institutions Matter.

[9] North, Wallis, and Weingast, Violence and Social Orders, 111. While this statement is largely correct, especially for ideal-type regimes, we will discuss a more complex view of the cooperation of political and economic elites in Chapter 5, too [→ 5.3].

[10] Hale, Patronal Politics, 19–22.

[11] Hale, 21. We use the adjective “multi-pyramid” in various contexts, but always with the same meaning: that no social group dominates over all the other groups.

[12] Hale, 64.

[13] Voslensky, Nomenklatura.

[14] Eisenstadt and Roniger, “Patron—Client Relations as a Model of Structuring Social Exchange,” 50.

[15] Lakner, “Links in the Chain.”

[16] Ledeneva, Can Russia Modernise?, 30.

[17] See, respectively, Moore, “The Structure of a National Elite Network”; Heemskerk and Fennema, “Network Dynamics of the Dutch Business Elite.”

[18] Reh, “Is Informal Politics Undemocratic?”

[19] Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die. On autocratic tendencies, see Chapter 4 [→ 4.4.1].

[20] Levitsky and Ziblatt, 72–96.

[21] Ledeneva, How Russia Really Works, 20–22.

[22] Helmke and Levitsky, “Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics.”

[23] Hale, Patronal Politics, 21.

[24] Voslensky, Nomenklatura.

[25] Markus, “The Atlas That Has Not Shrugged,” 101–2.

[26] Lamberova and Sonin, “Economic Transition and the Rise of Alternative Institutions.”

[27] Cf. Markus, Property, Predation, and Protection.

[28] Markus, “The Atlas That Has Not Shrugged,” 105–7.

[29] Tilly, Trust and Rule, 32.