Theories of post-communist states that are based on concepts presuming the societal interest principle necessarily have blind spots toward a large array of phenomena, stemming from such elements as the self-interested patronal elite and the systemic distortion of centralized/monopolized forms of corruption. Indeed, the latter are constituent elements of post-communist regimes. Disregarding these components leads to the same kinds of errors as if one were trying to understand a football match while disregarding the ball: in both cases, the phenomenon that gives sense to most of the game is missing from the picture.

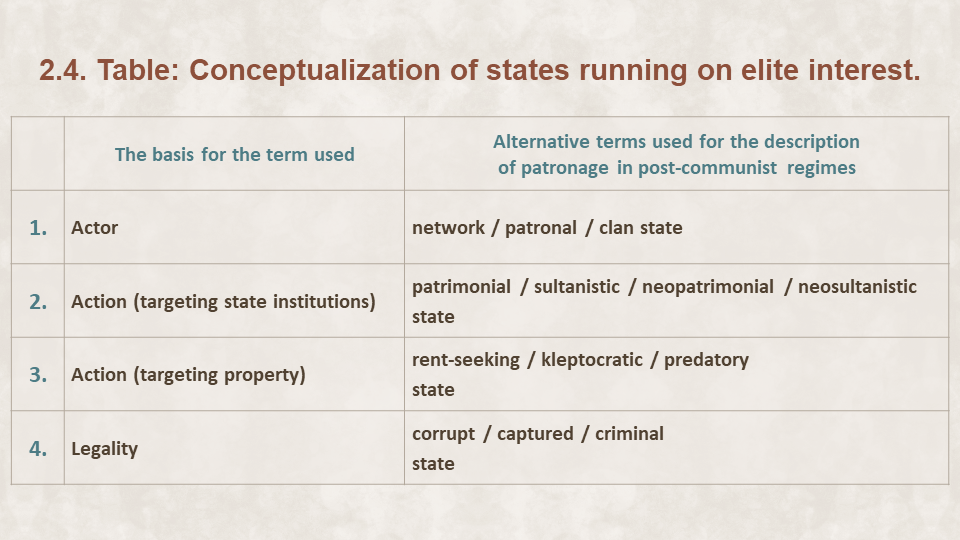

Several labels that have been developed for post-communist (and other) states take the principle of elite interest as their basis. The problem with the literature using them, therefore, has not been the blindness to the related phenomena but that they did not treat them as part of a larger analytical framework. Indeed, concepts like “network state” and “clan state” or “predatory state” and “kleptocracy” have been used almost as synonyms, not realizing that (1) these adjectives indeed refer to different concrete features and, therefore, (2) these concepts can be put in a coherent logical order.

To perform the logical ordering, we need to identify certain dimensions that these concepts reflect on. The dimensions can be found by relying on the stubborn-structures argument, especially Figure 1.4 from the previous chapter that showed the specificities of post-communist rulership [→ 1.5.1]. In that figure, we saw two chains of consequences, the first of which regarded personal relations. Accordingly, we may isolate the first dimension of the state, expressed in interrogative form:

- What is the nature of the ruling elite?

The second chain was concerned with institutional consequences. For we are in the principle of elite interest, we can formulate the question regarding the next dimension as follows:

- What is the action for elite-interest based appropriation of state institutions?

The two chains of consequences added up to a systemic distortion, namely centralized and monopolized forms of corruption (which is to be defined in general as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain [→ 5.3.2.1]). This phenomenon can be approached from two angles. On the one hand, we can focus on the corrupt action itself, where property is diverted to the hands of the elite (and its beneficiaries) via the state machinery. The appropriate question is the following:

- What is the action for elite-interest based appropriation of property?

On the other hand, corruption can be analyzed by its relation to the state. The attitude of the state towards corruption ranges from inimical to supportive, which is expressed in the law and its enforcement [→ 4.3.4-5, 5.3.4.2]. In other words, corruption moves on a scale from being incongruent with the state’s legal framework and relying on it, yielding the final question about a state dimension:

- What is the legal status of the elite-interest based action?

Resolving the prevalent incoherent and random use of terminology, we organize existing concepts from the literature along these four dimensions in a logical order. Ordering will happen as follows. Starting from the general definition of the state, we develop, step-by-step, more and more complex answers for each question along what we call interpretative layers. This means that, at each of the four dimensions, we take “state” first, and then we add a new characteristic feature to it, expressed by an adjective added to “state.” Next, we add one more feature and change the adjective accordingly. This process is continued until we reach the most extreme concept of state which is still relevant in the post-communist region (Table 2.4).

The closest resemblance to the method of interpretative layers is the ladder of abstraction, introduced to comparative politics by Giovanni Sartori,[1] by which the narrower classes of phenomena we want to define, the more specifying features we need to add to its definition. However, we prefer the term “interpretative layer” to Sartorian language because we believe it is more expressive. First, the result of this exercise will be a set of clear-cut categories, by which one can interpret the state feature by feature. Second, the categories are indeed layered on, or building on the definitions of each other, which means that they should neither be used interchangeably nor regressively. More abstract categories (composed of fewer layers) should be disregarded if the respective state satisfies the definition of a less abstract concept (composed of more layers).

[1] Sartori, “Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics.”